Hello, and welcome to the unofficial start of summer!

Hopefully everyone had a restful and reflective few days over the Memorial Day weekend. Memorial Day gives us the opportunity to recognize our military personnel that gave their lives in service to our country for our freedoms. Let’s always keep our veterans and active military personnel top of mind.

Other interesting happenings: Pam recently attended FMCSA’s Our Roads Our Safety® Week during the open house at the USDOT office in Washington DC. If you have any seat belt naysayers in your life, share the video from CAB’s LinkedIn post on her “seat belt convincer” experience.

Chad Krueger and Pam Jones

Events

CVSA, Commercial Vehicle Safety Alliance’s Operation Safe Driver Week is right around the corner focusing on reckless, careless, or dangerous driving. July 7 – 13 law enforcement in Canada, Mexico, and the U.S. will be on a more heightened awareness for both passenger vehicle drivers and CMV drivers engaging in unsafe behaviors.

CAB Live Training Sessions

Due to travel and PTO schedules we have only one session this month.

Tuesday, June 18th | 12p EST

BASICs Calculator | Chad Krueger

Expand your transportation safety expertise and help your clients & prospects understand the behaviors driving their BASICs and ISS values.

To register for the webinars, sign into your CAB account. Then click live training at the top of the page to access the webinar registration.

Explore all of our previously recorded live webinar sessions in our webinar library.

Follow us on the CAB LinkedIn page and Facebook.

CAB’s Tips & Tricks

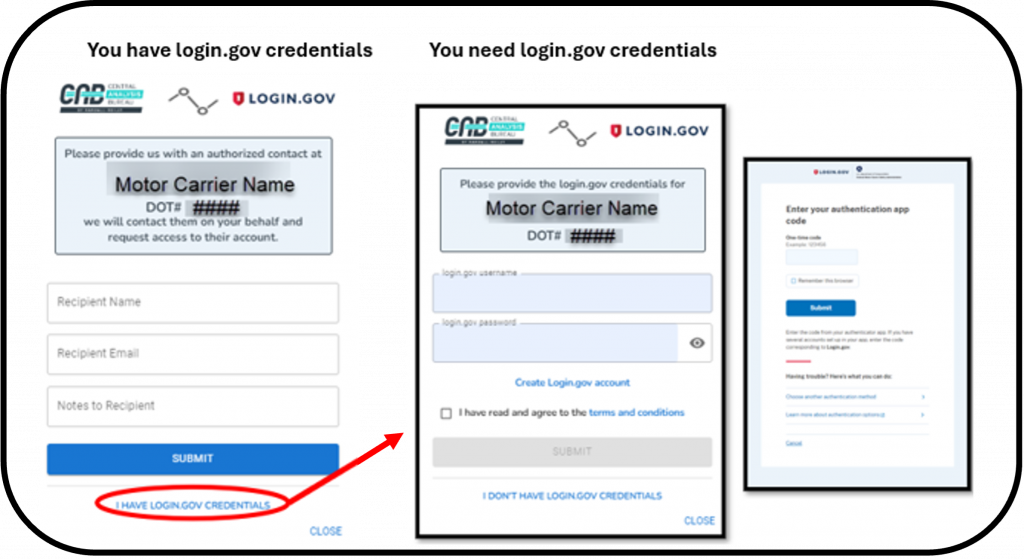

As you may already be familiar with, FMCSA implemented multi-factor authentication, MFA. MFA is a crucial feature we all experience if we do any kind of online business activity. Think of your banking, investment, utilities, travel, and all other kinds of online service transactions. CAB has added a link within our platform to replace the fleet’s ability to connect their driver data to our system. See the images below for login examples.

THIS MONTH WE REPORT

Commercial P/C Premiums Increase 7.7% in Q1 2024 The Council of Insurance Agents and Brokers reported that commercial property/casualty premiums rose by 7.7% on average in the first quarter of 2024. This marks the 26th consecutive quarter of increases. Read more…

Fleets’ earnings in the first quarter reveals market keeps getting weaker The first quarter of 2024 showed a continuing decline in the freight market with soft rates, low volume, and challenging weather impacting carriers. While some carriers like XPO exceeded expectations, others like Knight-Swift and Heartland Express faced significant losses. Read more…

Cyberattacks Over Work Email Most Used; Ransomware Hits Victims Hard A survey by Arctic Wolf reveals that business email compromise is now the leading method of cyberattack, with 70% of senior IT and cybersecurity decision-makers reporting attempts. Ransomware remains a primary concern, with 45% experiencing attacks in the past year. Read more…

Broker group takes on trucking’s crime epidemic, double brokers The Transportation Intermediaries Association (TIA) is leading an industry-wide fight against freight fraud, highlighting a 600% increase in freight fraud incidents. Their new 40-page “Framework to Combat Fraud” outlines five types of theft and preventive measures. Read more…

Marijuana rules and regs changing? What truckers need to know President Biden’s administration is pushing to reschedule marijuana to a Schedule III controlled substance. This move would acknowledge marijuana’s medical value and reduce its abuse potential. However, changes in marijuana policy for the trucking industry are not imminent. Read more…

Trailer orders indicate a ‘year of transition,’ forecast affected by overcapacity April trailer orders remained steady at 13,700 units, up 20% year-over-year, per ACT Research. Despite this, low trucking profitability and overcapacity challenge growth. ACT anticipates improved fleet profitability later this year, though investments might shift to new power units ahead of EPA’s 2027 regulations. Read more…

Surge of cargo theft is ‘hitting us like lightning,’ experts say Cargo theft rose by over 46% in Q1 2024, with incidents totaling 925 and an average stolen shipment value of $281,757. Fraud and forgery are common methods, impacting various commodities. Read more…

June 2024 CAB Case Summaries

These case summaries are prepared by Robert “Rocky” C. Rogers, a Partner at Moseley Marcinak Law Group LLP.

AUTO

Reeves v. Hertz et al., 2024 La. App. LEXIS 882, C.A. No. 23-494 (La. Ct. App. May 22, 2024). In this appeal arising from a chain-reaction accident, the Louisiana appellate court affirmed the trial court’s grant of summary judgment to two sets of motor carrier defendants. The trial court had found neither could have been the cause-in-fact of the plaintiff’s accident. On December 6, 2015, plaintiff Robert Reeves (“Reeves”) was traveling westbound on Interstate 10 in St. Martin Parish on the Atchafalaya Basin bridge. Reeves was driving a tractor trailer. Also traveling westbound on Interstate 10 were the following relevant vehicles: (1) a Ford Expedition driven by Jesus Torres pulling a trailer (“the Torres vehicle”); (2) a tractor trailer driven by Cullen Toole and owned by CTG Leasing (collectively “CTG”); (3) a tractor trailer driven by Owens, owned by Swift Transportation Company of Arizona, L. L. C., and insured by Red Rock Risk Retention Group, Inc. (collectively “Swift”); (4) a tractor trailer driven by Jorge Gonzalez-Puron; (5) a tractor trailer driven by Ronald Huff and owned by Royal Trucking Company; (6) a tractor trailer driven by Jason Bingham and owned by Ashley Distribution Services, Limited; and (7) a tractor trailer driven by Christopher Hertz, owned by Vela Transportation, and insured by Acuity Mutual Insurance Company (collectively “Hertz”). From these vehicles two separate but related motor vehicle accidents occurred. The initial collision (the “CTG collision”), occurred between CTG and the Torres vehicle. CTG was in the right lane of travel behind the Torres vehicle but noticed that the rear wheel of the Torres vehicle had begun wobbling. CTG moved into the left lane, even though tractor trailers are prohibited from using the left lane while moving across the Atchafalaya Basin. Then the rear wheel fell off the Torres vehicle. The loss of the wheel caused the Torres vehicle to lose control, collide with the right bridge railing, swerve into the left lane, and jackknife. This caused a collision between CTG and the Torres vehicle. The Torres vehicle came to rest blocking both westbound lanes of travel. At the time of the first CTG collision Swift, after traveling in the left lane, had returned to the right lane of travel eight to twelve seconds prior to the second collision. Upon seeing the first collision, Swift applied the brakes and came to a complete stop without impacting CTG, the Torres vehicle, or a Volvo that also came to a complete stop behind the CTG collision. Swift was being followed by five tractor trailers driven by Gonzales-Puron, Huff, Bingham, Reeves, and Hertz, respectively. Upon seeing the vehicles in front of them attempt to stop, each driver unsuccessfully attempted to stop. What followed was a series of collisions involving each of the other five tractor trailers, resulting in the Gonzales-Puron vehicle, immediately behind Swift, to be propelled into the rear of the Swift vehicle (the “Swift collision”).

Reeves filed his petitions for damages and various supplementations, alleging personal injuries, and naming the drivers, employers, and insurers of the four other tractor trailers involved in the second set of collisions, along with the parties involved in the initial collision between Swift and the Torres vehicle. After noting that Swift could effectively “shift the burden” to Reeves to show factual support sufficient to establish the existing of a genuine issue of material fact, the court found that Swift had effectively shifted the burden and Reeves failed to come forward with the necessary factual support for his claim against Swift. The appellate court agreed with the trial court that any chain of events between the initial CTG collision involving CTG and the Torres vehicle and the second collisions, Swift collision, was broken when Swift was able to come to a complete stop in the right lane of travel without impacting any vehicles involved in the initial collision. Reeves’ alleged injuries were the result of a separate, six-vehicle collision. This second collision did not involve either vehicle from the initial collision between CTG and the Torres vehicle. The court found that the evidence established Swift had re-established his vehicle in the right lane of travel for eight to twelve seconds before the second set of collisions, and that the Swift vehicle had come to a complete stop without impacting any other vehicle involved in the initial collision. The court rejected that that the mere statutory violations of Swift speeding and temporarily being in the left lane—where tractor trailers were prohibited—had no bearing on either accident. As such, the court found Reeves could not carry his burden to establish any action by Swift was a cause-in-fact of his injuries.

With respect to CTG, the court similarly upheld the trial court’s grant of summary judgment on lines very similar to those with respect to Swift. It found any chain of events from the CTG collision and the Swift collision was broken when Swift was able to come to a complete stop in the right lane of travel without impacting any vehicles involved in the initial collision. Reeves’ alleged injuries were the result of the separate, six-vehicle collision. This second six-vehicle collision did not involve either vehicle from the initial collision between CTG and the Torres vehicle. Similarly, Reeves’ reliance on statutory violations by CTG for traveling in the left lane and speeding was deemed insufficient due to the lack of causal relation on the collision and resulting alleged injuries to Reeves, given that the chain of events between the initial collision and the second collision was broken when Swift came to a complete stop without striking any vehicles involved in the initial collision. Accordingly, the appellate court determined Reeves could not carry his burden of proof at trial that CTG’s actions were a cause-in-fact or legal cause of Reeves’ alleged injuries. As such, it affirmed summary judgment in favor of CTG.

Team Indus. Servs. v. Most, 2024 Tex. App. LEXIS 3389, C.A. No. 1-22-00313 (Tex. Ct. App. May 16, 2024). In this appeal, the Court of Appeals of Texas vacated a jury award against a trucking company after the trial. The court made various other rulings not in keeping with the trial court. The appellate court, in sum, held the trial court erred under the Restatement (Second) of Conflict of Laws in applying Texas law instead of Kansas law to hold appellant responsible for 100 percent of the damages, despite the jury’s findings that appellant was ninety percent liable, because Kansas held a more compelling interest than Texas in holding all parties responsible. The appellate court also held appellant was entitled to a forum non conveniens dismissal, as it was unable to subpoena Kansas state regulators to testify about the results of any investigation into the accident. Furthermore, dismissal would not result in unreasonable duplication of litigation, given that it had already been established that the trial court erred in applying Texas law to certain of appellee’s claims. Accordingly, the $222 million verdict in favor of appellee was vacated and the case dismissed on forum non conveniens grounds.

Gruver v. Montesa Express, Inc. et al., 2024 U.S. Dist. LEXIS 79508, C.A. No. 1:21-cv-1210 (C.D. Ill. May 1, 2024). In this personal injury action arising from a motor vehicle accident, the trial court granted summary judgment on all counts in favor of the owner of a chassis that had been leased to a chassis pool cooperative at the time of the accident. TCW, who moved for summary judgment, is an “asset leasing company and equipment owner” which owned the chassis, or the base frame, attached to the tractor involved in the accident. The chassis (identified as “TCWZ 417132”) was leased as a part of a Master Lease Agreement between TCW and North American Chassis Pool Cooperative (“NACPC”). The equipment was then placed by NACPC into the Chicago-Ohio Valley Consolidated Chassis Pool LLC (“COCP”) to be used by various motor carriers. Pinoy Trucking signed a Uniform Intermodal Interchange Agreement (“UIIA”) with the chassis pool. Through this agreement, Pinoy Trucking gained access to the chassis and used it to transport a shipping container on the day of the accident. Pinoy Trucking employed Anthony Dunn, who was assigned as the driver of the tractor, which pulled the chassis and container on the day of the accident. Following the accident, the plaintiff filed suit against TCW alleging negligent hiring, entrustment, and maintenance. As for the negligent entrustment claim, under applicable law, the plaintiff was required to show “TCW ‘gave another express or implied permission to use or possess a dangerous article or instrumentality which [defendant] knew, or should have known, would likely be used in a manner involving an unreasonable risk of harm to others.’” The court found that in this instance, the chassis at issue was leased as a part of an agreement to lease over one thousand pieces of equipment to NACPC, which then placed the equipment into a chassis pool. It found “[t]here are no facts submitted by Plaintiffs that demonstrate TCW was involved with any day-to-day operations concerning the chassis, or that it had any knowledge of who was using it on the day of the accident. The undisputed facts fail to establish that Dunn was an employee, agent, or otherwise in service to TCW. The Court agrees with TCW that no reasonable jury could find it liable for negligent entrustment under these circumstances because there is not enough evidence to support a finding of implied permission.” The court similarly rejected plaintiffs’ argument that TCW had a duty to ensure the motor carriers that were part of the chassis pool had adequate safety records, noting that TCW had no direct contact with any motor carrier prior to the accident and resulting lawsuit. In the court’s view, adopting plaintiff’s version of negligent entrustment would be akin to imposing strict liability. Similarly, the court rejected the plaintiffs’ attempts to allege a common law duty upon TCW to all motorists, as the equipment lessor. The court explained there was no evidence that the chassis itself presented any danger to motorists absent independent, actionable negligence of the driver/motor carrier. It further noted that TCW lacked the ability to control or direct the conduct of Pinoy Trucking and Dunn. As such, there was no basis for a common law duty against TCW. The court also rejected plaintiffs’ attempts to hold TCW liable under the FMCSRs. It found TCW, in the capacity that it operated in this instance, was not a motor carrier subject to the FMCSRs. The court also rejected the plaintiffs’ attempts to hold TCW vicariously liable for the negligence of the other defendants, finding that such was precluded by application of the Graves Amendment. Finally, since the remaining loss of consortium claim against TCW was a derivative claim for which the court already held TCW was entitled to summary judgment, TCW was also entitled to summary judgment on this claim.

Nevil v. Western Dairy Trans., L.L.C., 2024 U.S. Dist. LEXIS 92518, C.A. No. 4:24-cv-279 (E.D. Tex. May 23, 2024). A motor carrier’s attempts to remove a personal injury action based upon FAAAA preemption and/or federal question jurisdiction was rejected by the Texas federal court. Accordingly, the matter was remanded to state court for further proceedings. The court rejected that FAAAA was complete preemption sufficient to sustain federal jurisdiction and the FAAAA defense did not present a federal question sufficient to establish independent federal question jurisdiction.

Ubaldo v. F&A Border Transp., LLC, 2024 U.S. Dist. LEXIS 79824, C.A. No. 24-CV-47 (W.D. Tex. May 1, 2024). A freight broker, motor carrier, and CMV driver’s attempts to remove a personal injury action to federal court premised upon FAAAA preemption and/or federal question jurisdiction were rejected and the case was remanded to state court for further proceedings. The court rejected that FAAAA was complete preemption sufficient to sustain federal jurisdiction and the FAAAA defense did not present a federal question sufficient to establish independent federal question jurisdiction.

Dove v. Gainer, 2024 U.S. Dist. LEXIS 82016, C.A. No. 1:22-cv-00754 (N.D. Ala. May 6, 2024). In this personal injury action arising from a motor vehicle accident, claims of wantonness and negligent training and supervision were dismissed with prejudice. The accident that formed the basis of the suit occurred as a tractor-trailer operated by Gainer was merging onto I-20 when it collided with the plaintiffs’ vehicle. Gainer had been a commercial truck driver for six years at the time of the accident. He had never been cited for a moving violation. He did once damage the driver-side door of a commercial vehicle when the door contacted a fence as he was backing out of a property. Additionally, he had been reprimanded and counseled for driving beyond the hours allowed by the Federal Motor Carrier Safety Administration. However, he was within the hours-of-service limitations at the time of the accident. The court explained that under applicable state law, to hold a defendant liable for “wanton conduct” the plaintiff must establish a “high degree of culpability” and “inattention, thoughtlessness, heedlessness, or lack of due care”, alone, is insufficient. Rather, “[w]antonness requires proof of ‘the conscious doing of some act or the omission of some duty while knowing of the existing conditions and being conscious that, from doing or omitting to do an act, injury will likely or probably result.’” Under the undisputed facts of this accident, the court held it failed to establish the requisite degree of reprehensibility to sustain a wantonness cause of action and dismissed the wantonness claim with prejudice.

As for the negligent training and supervision claim, Alabama law required “plaintiff to show an employer knew or should have known its employee was incompetent.” Gainer being at fault for no more than one accident in the six years he had worked as a commercial truck driver was insufficient, in the court’s view. Similarly, the prior HOS violation, was immaterial since it was undisputed he was properly within the HOS at the time of the Accident. The HOS violation, standing alone, did not create a genuine issue of material fact as to Gainer’s competence as a driver. As such, this claim was also dismissed with prejudice.

Summerfield v. S.E. Freight Lines, Inc., 2024 Ark. App. 326, 2024 Ark. App. LEXIS 352, C.A. No. CV-23-12 (Ark. Ct. App. May 22, 2024). In this loading dock accident, the Court of Appeals of Arkansas affirmed summary judgment in favor of the motor carrier and its driver. The trial court dismissed with prejudice the plaintiffs’ negligence case against defendants and their negligent hiring, training, and supervision claims against the motor carrier as well as the plaintiffs’ request for punitive and compensatory damages. Plaintiff was employed as a forklift operator by R&R Packaging and was loading and unloading tractor trailers at one of R&R’s warehouses. Williams, the driver of the tractor-trailer on behalf of Southeastern, backed a Southeastern truck up to the R&R warehouse. There was conflicting testimony as to whether Williams set his air brakes, but Williams testified that it was his practice at the warehouse to chock his highway truck’s wheels once parked at the loading dock. However, neither OSHA nor R&R permitted highway trucks to be loaded or unloaded after air brakes were heard to be deployed. Instead, each required a highway truck’s wheels to be chocked—a wedge placed behind the wheels—before loading or unloading cargo. Plaintiff, who evidently was about to go onto break, placed a foot on the back-end of the trailer, keeping one foot on the dock before Williams exited his truck and chocked the wheels. Unaware that Plaintiff was trying to board the trailer before Williams had stopped and chocked the wheels, Williams repositioned Southeastern’s tractor. During this maneuver, plaintiff fell from the loading dock, sustaining injuries to his finger and arm. Plaintiff sued, alleging Southeastern was vicariously liable for Williams’s alleged negligence and claimed Southeastern was directly liable for negligent hiring, negligent training, and negligent supervision. The plaintiffs sought compensatory as well as punitive damages as a result of Williams’s and Southeastern’s willful and wanton conduct. Following discovery, Williams and Southeastern moved for summary judgment. The appellate court found the trial court correctly granted summary judgment to Williams and Southeastern because “as a pure matter of law,” Williams owed plaintiff no duty because plaintiff’s conduct was not reasonably foreseeable insofar as it was in violation of R&R’s own company policies and OSHA regulations. Further evidence presented showed R&R determined plaintiff was distracted and violated his employer’s policy. Because plaintiff’s conduct leading up to the incident was outside the accepted practice both of the industry in general and that of this employer, there is no way Williams could have reasonably foreseen it. Further, the plaintiffs introduced no evidence below showing that Williams could have foreseen plaintiff’s conduct. Thus, absent any duty owed to plaintiff, all negligence-based claims were due to be dismissed.

Velilla v. Rushing, 2024 U.S. Dist. LEXIS 91263, C.A. No. 4:23-cv-03009 (S.D. Tex. May 21, 2024). A lessor of a tractor involved a accident successfully moved under the Graves Amendment to be dismissed from a personal injury action alleging various causes of action against it.

Perry v. Cummings, 2024 U.S. Dist. LEXIS 86340, 2024 WL 2171934, C.A. No. 1:22-cv-3860 (N.D. Ga. May 14, 2022). Various motor carrier and transportation defendants successfully moved for summary judgment on plaintiff’s negligent hiring, supervision, and entrustment claims. At the time of the accident, Cummings was operating a tractor-trailer for defendant Ryan Transport, LLC, who was assigned to transport the load by defendant Lenk Express, LLC. Ryan hired Cummings in June 2020, and Cummings was not involved in any accidents, nor did he receive any citations or points on his CDL license, prior to the accident in question that occurred in March 2021. Prior to his employment with Ryan, Cummings received two speeding tickets and a citation for following too closely between 2015 and 2017. Lenk Express moved for summary judgment as to the negligent supervision claim against it, whereas Ryan Transport moved for summary judgment as to the negligent hiring and supervision claims against it. The court agreed, finding “traffic citations that occurred more than three years before a driver was hired in no way implicate any potential negligent supervision of that driver. And second, ‘no reasonable jury could find that a truck driver was accident-prone based on two speeding tickets and a citation for following too closely over the course of a decade.’” As such, it granted summary judgment on these causes of action in favor of defendants.

In re Mesilla Valley Transp., 2024 Tex. App. LEXIS 3147, 2024 WL 2034732 (Tex. Ct. App. May 8, 2024). In this appeal of a discovery dispute on mandamus, the Court of Appeals of Texas curtailed a tort plaintiff’s discovery requests, and in so doing, reversed the trial court’s order. The personal injury suit arose out of a July 12, 2021, motor vehicle accident involving a MVT tractor-trailer operated by its driver, Stowbridge. In discovery in the personal injury action, the plaintiff sought information about lawsuits involving MVT for the past ten years and requested access to Stowbridge’s cell phone to retrieve data for four hours before and around the time of the collision. The trial court ordered MVT to produce information for all personal injury matters involving truck wrecks from July 12, 2017, to the present. The appeals court found both of these requests to be too broad. With respect to the prior accidents/lawsuits, it explained plaintiff “makes no effort to justify why lawsuit information involving MVT from July 12, 2017, to the present advances his claims against MVT.” Further, it found the trial court’s order as to prior personal injury matters failed to show how the scope of the ordered information to be produced “is refined in time, location, and scope as to be within the bounds of permissible discovery.” As for the cell phone records request, the court found while plaintiff may be entitled to discover Stowbridge’s cell phone data for some period of time, “the trial court’s order is not limited in temporal scope to be tailored to encompass only the time period in which Stowbridge’s cell phone use could have contributed to the collision.” It specifically noted that plaintiff’s mandamus response and motion to compel failed to establish why he needed Stowbridge’s cell phone data four hours before the collision to prosecute his lawsuit. Further, the appeals court found the trial court’s order failed to encompass the type of privacy protections necessary to ensure Stowbridge’s privacy interests were protected from unnecessary disclosure.

Quality Express, LLC v. Crane Transp., LLC, 2024 U.S. Dist. LEXIS 81186, C.A. No. 8:21-cv-02159 (D.S.C. May 3, 2024). In this action arising from a tractor-trailer on tractor-trailer accident, the trial court granted summary judgment to the company whose tractor trailer was parked on the side of the roadway. he accident occurred at approximately 2:45 a.m. on Interstate 85. Plaintiff’s driver collided with the rear of the tractor-trailer owned by defendant but which was parked in the emergency lane of the interstate. Plaintiff filed a complaint, asserting causes of action for negligence/negligence per se, negligent entrustment, and negligent hiring, supervision and retention. On summary judgment, defendants contended that plaintiff had no evidence to deny summary judgment because plaintiff had not served any discovery requests, identified any expert witnesses, or taken a single deposition. Defendants contended plaintiff had thus failed to come forward with evidence to refute their claims that plaintiff’s employee acted negligently in crossing over the fog line, and certainly had failed to come forward with evidence sufficient to support the direct negligence claims against the motor carrier. In response, plaintiff argued, lack of discovery notwithstanding, it was entitled to argue defendant’s employee was negligent in parking the tractor-trailer on the side of the interstate in a non-emergency situation, and moreover, it was entitled to cross-examine defendant’s theory of liability at trial. Ultimately, the trial court agreed with defendants. It held, “[w]hile Plaintiff argues that Defendants acted negligently, it has presented no evidence to support any element in the causes of action listed in the Complaint. Although Plaintiff claims it is undisputed that Defendant Hart parked the tractor trailer on the shoulder of Interstate 85 without employing required precautions, there is no evidence in the form of affidavits, depositions, stipulations, admissions, or otherwise to support that claim. Similarly, none of Plaintiff’s claims against Defendants are supported by any identifiable evidence.” As such, it granted summary judgment to defendants.

BROKER

Hamby v. Wilson, 2024 U.S. Dist. LEXIS 90897, C.A. No. 6:23-cv-249 (E.D. Tex. May 21, 2024). In this instance, the court agreed that claims of negligent broker and negligent selection of a motor carrier were preempted by FAAAA. After noting the three tests that have developed nationwide in addressing the scope of FAAAA preemption for personal injury/tort claims against brokers, the court found the third test—which holds that “§ 14501’s express preemption applies to state tort claims and that the safety exception does not save them from preemption” to be “the most persuasive because [it] most clearly honor[s] the statutory text.” As such, the court agreed with the broker and dismissed the negligent broker and negligence selection of motor carrier causes of action against the broker.

CARGO

Minder LLC v. Real Int’l SCM Corp., 2024 U.S. Dist. LEXIS 84046, C.A. No. 2:23-cv-3292 (C.D. Cal. May 8, 2024). In this freight damage lawsuit, the court denied a defendant’s motion to dismiss premised upon insufficient allegations of carrier liability. The operative complaint alleged the moving defendant “was part of a series of subcontractors for the transport of the goods at issue.” In the court’s view, the motion to dismiss was “premised on the idea that only a defendant who actually physically transports the cargo at issue can be liable as a ‘carrier’ under the Carmack Amendment.” The court rejected this premise, instead finding “the term ‘carrier’ is not limited to entities that physically carried the goods. Instead, courts have focused on whether an entity ‘legally binds itself to transport’ and ‘accept[s] responsibility for ensuring delivery of the goods.’ In other words, a defendant can be liable as a carrier in some circumstances even if that defendant subcontracted out its assumed responsibility for transporting the goods at issue.” Under this standard, the court found the operative complaint alleged sufficient facts to preclude dismissal and refused to require specific factual allegations of the defendant’s precise role in the transportation at the pleading stage.

Lotte Ins. Co. v. R.E. Smith Enters., 2024 U.S. Dist. LEXIS 83430, 4:23-cv-153 (E.D. Va. May 7, 2024). In this suit alleging damage for a large shipment of lithium ion batteries, various defendants were granted dismissal at the pleadings stage. The facts established that in October of 2021, Samsung SDI Co., Ltd. (“Samsung”) shipped a container of 300 packages of large capacity cell lithium-ion batteries (the “Batteries”) from South Korea, Samsung’s country of incorporation. Traveling overseas on the vessel “Cosco Shipping Lotus,” the Batteries were ultimately destined for a buyer in Alberta, Canada, but first arrived on November 21, 2021, at Virginia International Gateway (“VIG”), a container terminal in Portsmouth, Virginia. Plaintiff alleges that in December of 2021, Lotte Global Logistics Co., Ltd. (“Lotte”) contracted with defendant Smith, a logistics business, to deliver the Batteries overland to the Canadian buyer. According to a series of emails exchanged between Lotte and Smith around December 3, 2021, Smith was to receive the Batteries from VIG, transload the Batteries from their ocean-going container, and then transport the Batteries to their Canadian buyer consistent with the applicable safety rules and regulations for shipping flammable lithium-ion batteries. Because the ultimate destination for the Batteries was outside of the United States, the foregoing procedures “needed to occur from a bonded warehouse.” Smith therefore selected the nearby “Trinity Logistics/DNK Warehouse” (“Warehouse”), located in Hampton, Virginia, and subcontracted with defendants Trinity Logistics LLC (“Trinity”) and DNK Warehousing & Trucking LLC (“DNK”) on behalf of Lotte for the “safe handling, transloading, storage, and redelivery of the Batteries.” Accordingly, between December 8th and 11th, the Batteries entered the Warehouse in “good order and condition, and were accepted as such.” plaintiff alleges that, at all “relevant times Trinity and DNK leased the Warehouse from its owner, G Street, another named Defendant. While temporarily stored in the Warehouse, the Batteries were allegedly under DNK’s and Trinity’s “exclusive custody and control,” and were scheduled to be transferred to a different container appropriate for ground transportation to Canada. However, around December 12, 2021, plaintiff alleges that the Batteries, while still “in DNK’s and Trinity’s exclusive custody and control,” suffered “physical and wetness damage” due to both the collapse of the Warehouse’s outer wall and the water discharged from a burst pipe. Ultimately, upon final inspection, the batteries were deemed a total loss. The commercial value of the Batteries, by Plaintiff’s calculation, was approximately $493,800, and the cost of transportation, inspection, and disposal was approximately $49,380, producing a total loss of approximately $543,180. Plaintiff filed its complaint, asserting seven counts against defendants Smith, DNK, Trinity, and G Street.

Smith moved in response to the complaint, seeking dismissal of the bailment and negligence claims as preempted by the Carmack Amendment. While the operative complaint alleged alternatively that Smith was a carrier or broker, the court found Smith was entitled to dismissal because if it was a carrier the claims would be preempted by the Carmack Amendment, whereas if it was ultimately determined to be a broker with respect to the shipment, the claims would be preempted by FAAAA. With respect to the bailment claim, the court found that even if it was “contract-based” it would nevertheless be preempted by FAAAA. The court rejected that the bailment claim was a “routine breach of contract claim” and instead relied upon purported state-law based obligations, and as such, fell within FAAAA’s preemptive scope.

As for G Street, the court found the complaint failed to allege necessary factual support for a claim under Virginia law—namely that G Street had exclusive control over the batteries. It noted that the complaint specifically alleged that G Street leased the warehouse to DNK and Trinity and that DNK and Trinity exercised “exclusive custody and control” over the batteries. As such, the bailment claim failed. Similarly, the court found the negligence claim against G Street—as the owner of the Warehouse—failed under applicable Virginia law.

Ronate C2C, Inc. v. Express Logistics, Inc., 2024 U.S. Dist. LEXIS 92013, 2024 WL 2338262, C.A. No. 23-cv-01917 (S.D. Cal. May 22, 2024). In this cargo damage lawsuit, various defendants obtained dismissals in their favor at the pleading stage. The pleading alleged as follows: Plaintiff is a distributor of chemical supplies, equipment, and related services; plaintiff and defendant Express Logistics entered into a brokerage agreement in which Express “promised to identify and locate reputable, but cost-effective, carriers for Plaintiff’s shipping needs;” plaintiff asked Express to arrange for shipping of a $14,000 Rectifier from San Diego, California, to plaintiff’s client located in Sparks, Nevada; on Express’s recommendation, plaintiff hired defendant Clear Lane to ship the goods, but Clear Lane subcontracted with defendant AAA to serve as plaintiff’s carrier without plaintiff’s knowledge or consent; thereafter, plaintiff discovered that the Rectifier was not delivered to their client; Express informed plaintiff the Rectifier was lost. As a result, plaintiff filed a claim for breach of contract against Express and a claim for negligence against Express, Clear Lane, and AAA in the Superior Court of California, County of San Diego. AAA removed the case to federal court and thereafter moved for dismissal, contending plaintiff’s negligence claim against it is preempted by the Carmack Amendment. Clear Lane joined AAA’s motion. After citing established law, the court agreed with Clear Lane and AAA and held plaintiff’s negligence claim against each was completely preempted by the Carmack Amendment, and therefore each was entitled to dismissal in their favor, but with leave to plaintiff to amend.

Cal. Auto. Ins. Co. v. Colonial Van Lines, Inc., 2024 U.S. Dist. LEXIS 91305, C.A. No. 5:23-cv-0562 (C.D. Cal. May 20, 2024). In this property damage and subrogation lawsuit, the federal trial court denied a motion to dismiss based upon Carmack preemption. The court acknowledged that the defendant’s arguments for dismissal “hinge on whether the Carmack Amendment applies to Plaintiff’s Complaint.” While, in connection with its motion to dismiss, the defendant presented evidence that the move in question was interstate, the court held it was confined, at this stage, to the allegations of the complaint, which did not mention the interstate nature of the shipment. Rather, the complaint merely mentioned plaintiff contracted with defendant to transport his property “to an agreed upon location.”

Max Zach Corp. v. Marker 17 Marine, 2024 U.S. Dist. LEXIS 88529, 2024 WL 2139614, C.A. No. 3:23-cv-01088 (D. Conn. May 14, 2024). In this lawsuit arising from the allegedly failed modification and interstate transport of a yacht, the trial court granted defendants’ dismissals with respect to certain causes of action alleged against each. According to the operative pleading, plaintiff contracted with defendant Marker 17 to modify its 2006 48’ Fountain yacht including retrofitting the yacht with new motors. Plaintiff alleges the contract price of $315,000 also required Marker 17 to be responsible for the delivery of the retrofitted yacht from Marker 17’s location in Wilmington, North Carolina to plaintiff’s location in Connecticut. Following the retrofitting, Marker 17 prepared the yacht for transport. Marker 17 selected Premium Carriers to perform the interstate transport. While in transit in New Jersey, the trailer containing the yacht overturned. Plaintiff alleges a total loss of $750,000. Following the accident, the yacht was transported to Superior Towing and Transport, which is allegedly charging storage fees of $150 per day, where it remains. Plaintiff alleged four causes of action: (1) negligence against Marker 17; (2) breach of contract against Marker 17; (3) conversion against Marker 17; and (4) Carmack Amendment cause of action against Premium Carriers. Marker 17 moved to dismiss the negligence and conversation claims against it. With respect to the negligence claim, the court first agreed with Marker 17 that under the applicable choice of law rules, Connecticut, not New Jersey law, applied and therefore plaintiff’s negligence claim was time-barred by the two-year statute of limitation. With respect to the conversion claim, the court agreed with Marker 17 that it was duplicative of the breach of contract claim already alleged against Marker 17. The court found that based upon the allegations of the complaint, it was clear that the conversion claim proceeded from and related to the alleged contract between Marker 17 and plaintiff, and accordingly, the breach of contract claim was the appropriate avenue for plaintiff to pursue recovery against Marker 17.

COVERAGE

Diamond Transp. Logistics, Inc. v. Kroger, Co., 2024 U.S. App. LEXIS 11561, C.A. No. 23-3462 (6th Cir. May 13, 2024). In this appeal, the Sixth Circuit affirmed the trial court’s ruling regarding the scope of an indemnification obligation between two parties to a transportation contract. Diamond and Kroger entered into a formal agreement, which provided, amongst other things the right of Kroger to withhold shipping payments from Diamond for claims it had against Diamond if certain conditions were met. The agreement also discussed indemnification. It stated:

[Diamond] does hereby expressly agree to indemnify, defend and hold harmless [Kroger], its affiliates and subsidiaries and their respective directors, officers, employees, agents, successors and assigns (“Indemnit[e]es”) from and against any and all suits, actions, liabilities, judgments, claims, demands, or costs or expenses of any kind (including attorney’s fees) resulting from (i) damage or injury (including death) to the property or person of anyone, whomsoever they may be, arising or resulting at any time or place from any operations hereafter performed either by [Diamond], its agents, employees or subcontractors in performing services for Kroger or (ii) the negligence, willful misconduct or violation of law by [Diamond], its agents, employees or subcontractors except to the extent that such liability is caused by the sole negligence or willful misconduct of Kroger.

In December 2015, one of Diamond’s subcontractors was involved in an accident with a minivan while hauling Kroger products through Missouri. The occupants of the minivan all were killed in connection with the accident. After the family of the decedents amended their complaint to add Kroger, alleging negligence and recklessness in selecting, hiring, and retaining Diamond; negligent/reckless selection as a shipper, Kroger tendered the lawsuit to Diamond and demanded defense and indemnification. Thereafter, Kroger and Diamond entered into an “indemnification agreement” whereby Diamond agreed to “indemnify and hold [Kroger] harmless from any claim or liability arising from” the December 2015 collision. Still, by June 2018, Diamond hadn’t reimbursed Kroger. Kroger reached out again, specifying its legal fees. But that demand, too, proved fruitless. Kroger then took matters into its own hands. Starting in July 2018, it withheld shipping payments from Diamond. Kroger ended up withholding nearly $1.8 million. Diamond quickly realized it wasn’t getting paid but didn’t know why. In a September letter to Diamond, Kroger explained: it thought Diamond was “obligated to defend and indemnify Kroger.” By failing to do so, Kroger said Diamond was breaching their agreements. Kroger stated that it would continue to withhold payment until things changed.

One month later, Diamond took action. Though its insurer refused to provide Kroger coverage, Diamond said it would “defend, hold harmless and indemnify Kroger” in the family’s suit per the parties’ transportation agreement. Diamond even retained local defense counsel for Kroger. But by then, according to Kroger, it was too late. Over the past year, Kroger’s counsel had interviewed several witnesses and handled extensive discovery requests. Further, within the next month, Kroger’s corporate designee would be deposed, and Kroger would mediate with the family. Diamond asked Kroger to delay mediation so it could get up to speed. But Kroger pressed on and settled with the decedents’ family for over $2 million.

By December 2019, Kroger still hadn’t paid Diamond the money it withheld. Diamond sued to try to recoup those funds. In response, Kroger filed claims of its own, including one for breach of the transportation agreement’s indemnity provision. Kroger sought the difference between what it withheld and what it ultimately settled the family’s claims for—roughly $600,000.

Both parties moved for summary judgment. Relevant here, as to Kroger’s claim for breach of the agreement’s indemnity provision, the district court ruled in Kroger’s favor and awarded it $612,429.45 plus interest. Diamond appealed.

On appeal, Diamond presented only one question: Was it required, under the parties’ transportation agreement, to indemnify Kroger for the family’s claim? According to the Court, no one disputed that the family’s claim triggered clause (i) of the indemnity provision, which indemnifies Kroger from damage or injury (including death) to a person while a Diamond subcontractor ships Kroger goods. Instead, the issue is whether the indemnity provision’s exception for “liability. . . caused by the sole negligence or willful misconduct of Kroger” relieves Diamond of its obligation. Applying Ohio law, the court found there was no evidence that Kroger’s liability was based upon Kroger’s “sole negligence” so as to trigger application of the exception to the indemnification obligation of Diamond under the contract. The Sixth Circuit held “Diamond’s negligence played at least a part in Kroger’s liability for the family’s claim. Claims of negligent selection, hiring, and retention take two to tango—negligent parties, that is. The claim’s elements tell the story. To succeed, a plaintiff must show, among other things, ‘the employer’s negligence in hiring or retaining the employee” and an “employee’s act or omission.’ Kroger’s liability, therefore, was ‘not viable without an underlying act of negligence by [Diamond].’Because Diamond must have also been negligent for Kroger to be liable, the ‘sole negligence’ exception does not relieve Diamond of indemnification.” As such, it held Kroger was entitled to indemnification in relation to the personal injury claims arising from the Accident and affirmed the trial court’s award in favor of Kroger.

WORKERS COMPENSATION

No cases of note to report this month.